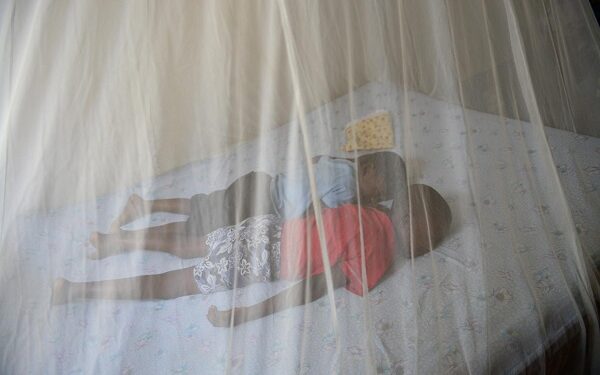

Accra, Sept 11 (The African Portal) – Malaria continues to cast a long, devastating shadow over Ghana and much of the tropical world, claiming hundreds of thousands of lives annually and placing an immense burden on our families and healthcare system. The World Health Organization’s (WHO) World Malaria Report 2022 highlighted that an estimated 619,000 malaria deaths occurred globally in 2021, with the African Region shouldering a staggering 95% of this grim statistic. In Ghana, the disease remains a leading cause of morbidity and mortality, particularly among our most vulnerable: children under five and pregnant women.

This already dire situation is projected to worsen under ongoing climate change scenarios. Leading scientific bodies like the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) have consistently warned that rising global temperatures and altered precipitation patterns are likely to expand the geographical range and lengthen the transmission seasons of malaria vectors, such as mosquitoes. Increased frequency of extreme weather events, like floods, can also create new breeding grounds, further proliferating vector populations. It is against this backdrop of an escalating threat that we must urgently diversify and strengthen our control strategies.

While we have relied heavily on insecticide-treated nets, indoor residual spraying, and antimalarial drugs, the time has come to bolster our arsenal with a powerful, sustainable, and climate-adaptive strategy: biological vector control, championed by natural allies like the dragonfly.

The principle is simple yet profound: instead of solely relying on chemicals, we can foster environments where natural predators of mosquitoes thrive. Dragonflies, both in their aquatic larval stage (nymphs) and as agile aerial adults, are voracious predators of mosquitoes. Research published in journals such as the Journal of Vector Ecology and numerous entomological studies confirm that dragonfly nymphs can consume a significant number of mosquito larvae in shared aquatic habitats, thereby reducing the emergence of adult, disease-transmitting mosquitoes.

Crucially, the effectiveness of these natural guardians is inextricably linked to the health of our local ecosystems. This is where a paradigm shift in our urban and peri-urban planning is urgently needed. We must actively maintain and restore natural wetlands, plant more indigenous trees and shrubs, cultivate diverse vegetation, and protect riparian buffers (the vegetated zones along rivers, streams, and water bodies) in and around our residential areas.

Moreover, embracing biological control, underpinned by robust ecosystem management, is a potent climate change adaptation strategy. Unlike chemical interventions which can face issues of insecticide resistance and environmental contamination, nature-based solutions are inherently more resilient and sustainable. Healthy, biodiverse ecosystems that support mosquito predators are also better equipped to handle climate stressors like extreme rainfall events, contributing to overall community resilience and mitigating some impacts of a changing climate.

Lamentably, current trends often see these vital green spaces cleared for construction, or neglected and turned into refuse dumps, inadvertently creating more breeding sites for mosquitoes while eliminating the habitats of their natural enemies. This approach is shortsighted. Well-maintained green infrastructure, as highlighted in various urban ecology studies, offers a cascade of benefits. Beyond vector control, these natural spaces are critical for flood mitigation – a crucial adaptation to climate change-induced erratic rainfall – acting as sponges that absorb excess rainwater. They improve air quality, reduce urban heat island effects, and enhance biodiversity.

The economic and social justifications for embracing biological control, supported by habitat conservation, are compelling. By naturally reducing mosquito populations, we can lessen the incidence of malaria. This translates directly into reduced expenditure on costly antimalarial drugs and hospitalizations for families, many of whom are already struggling financially. For the government, it means a lighter load on the national health budget, freeing up resources for other critical health interventions.

Most importantly, it means lives saved and a healthier, more productive populace, better able to withstand future challenges.

The responsibility for this ecological renaissance rests on multiple shoulders. City authorities, including Metropolitan, Municipal, and District Assemblies (MMDAs), must lead the charge. They need to integrate green infrastructure planning and climate adaptation principles into all development approvals, enforce bylaws that protect natural areas, and invest in the restoration of degraded wetlands and riparian zones. Public parks and community green spaces should be designed with ecological and climate resilience principles in mind.

Private landowners also have a significant role to play. By cultivating diverse gardens, planting native trees and shrubs, and avoiding the indiscriminate use of broad-spectrum pesticides that harm beneficial insects, they can transform their compounds into havens for nature’s pest controllers and contribute to local climate adaptation efforts.

The fight against malaria, especially in the face of climate change, requires a multi-pronged, integrated approach. Biological control, facilitated by the preservation and promotion of natural habitats, offers a cost-effective, environmentally sound, and sustainable complement to existing strategies, while simultaneously building our resilience to climate impacts. It is time for Ghana to look to the wisdom of nature, harness the power of allies like the dragonfly, and cultivate healthier, more resilient communities for generations to come. Let us invest in green, not just grey, infrastructure for a malaria-freer and climate-resilient future.