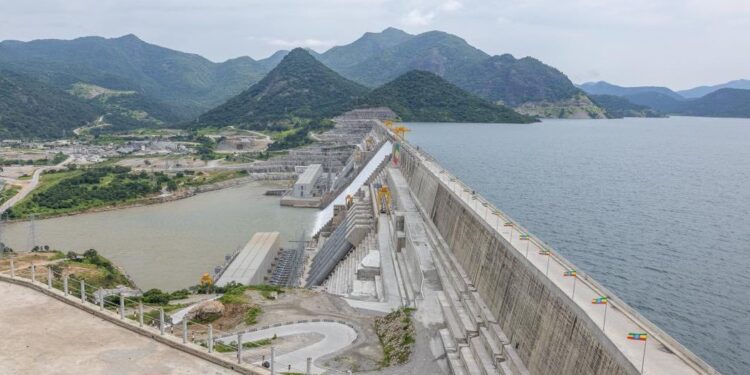

ACCRA, Sept 18 (The African Portal) – When Ethiopia spun up the last turbines of the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD), it didn’t just add megawatts to a national grid, it rewired expectations for Africa’s energy future.

The 5,150 MW hydropower colossus on the Blue Nile is now the continent’s largest power station. Two thousand miles west, Ghana’s Akosombo Dam (AD), a mid-20th-century project that created Lake Volta still anchors Ghana’s power system with 1,320 MW, a reminder that hydropower can be both transformational and fraught.

Together, these dams bookend six decades of African development: one born in the optimism of post-independence nation-building, the other in a 21st-century race to electrify economies and export power across borders. Their contrasts: capacity, footprint, diplomacy, climate risk offer a blueprint for what to emulate and what to avoid as Africa chases universal electricity access.

Capacity vs. Footprint

On raw generation, GERD overwhelms Akosombo about four times larger in installed capacity (5,150 MW vs. 1,320 MW). Yet the geography flips when it comes to water: Akosombo’s Lake Volta is among the largest human-made reservoirs on Earth at 148 billion m³ and 8,502 km² of surface area. GERD’s reservoir is 74 billion m³ and 1,874 km². The upshot is counterintuitive but crucial: GERD extracts more electricity per unit of flooded land, a better trade-off for land, livelihoods, and methane-emitting biomass.

Figure. GERD (Ethiopia) vs. Akosombo (Ghana): (a) capacity—5,150 vs 1,320 MW; (b) reservoir—74 vs 148 billion m³; (c) surface area—1,874 vs 8,502 km². Values shown on bars; legend centered. GERD delivers more power despite Akosombo’s larger reservoir and footprint.

For Ghana, Akosombo’s scale enabled aluminum smelting, grid expansion, and a new inland fisheries economy but also submerged villages and reshaped disease ecologies along emergent shorelines. For Ethiopia, GERD’s more compact footprint is an advantage; what matters now is how it’s operated.

Conflict, Cooperation, and the Politics of Rivers

Hydropower is never just engineering; it’s diplomacy in concrete. On the Nile, GERD sits atop a basin shared by 11 countries. Ethiopia views the dam as an overdue dividend of national sovereignty and a springboard for regional power trade. Egypt and Sudan worry about drought-time flows and insist on a binding operating framework. The truth is that both instincts are reasonable, and reconcilable. Long-term stability will depend on transparent data sharing, drought-sharing rules, and independent monitoring that moves the conversation from rhetoric to hydrology.

On the Volta, Akosombo avoided transboundary disputes but struggled with domestic governance: resettlement of roughly 80,000 people left deep social footprints, and emergency spillages in recent wet years inundated downstream communities. The lesson for GERD is simple: people and safety belong at the center of dam operations, not the margins.

Climate Change: Planning for Extremes, Not Averages

Both dams are entering an era of hydrological whiplash. Climate change is amplifying drought and flood cycles in the Sahel and East Africa, raising the stakes for how reservoirs are filled, drawn down, and spilled. Ghana has suffered painful episodes at both ends: drought-driven power shortages (“dumsor”) in dry years, and property-destroying spill releases in wet ones. Ethiopia, too, will face years when the Blue Nile swells and years when it stutters.

The operating playbook must evolve: adaptive rule curves, seasonal forecasts linked to dispatch, public dashboards for inflows/outflows, and early-warning systems downstream. The cost of forecasting and communication is minuscule compared to the social cost of getting it wrong.

Can GERD Close Africa’s Power Gap?

Not on its own, but it can move the needle. Between 600 and 750 million Africans still lack electricity. Urbanization, industrialization, and rising incomes will push demand steeply upward through the 2030s. GERD is a significant wedge: it doubles Ethiopia’s generation capacity, stabilizes domestic supply, and exports power to neighbors through the Eastern Africa Power Pool. That helps displace diesel and expand access if the power can flow to where it’s needed.

But even if GERD runs at high capacity and every cross-border line hums, Africa will still confront a daunting supply and reliability gap. The continent needs a portfolio: faster grid build-out, solar and wind at scale, flexible thermal or storage for balancing, and regional markets that dispatch lowest-cost power regardless of nationality. In that mix, large hydro remains a backbone technology, but not the only vertebra.

The Next Frontier: Congo’s Inga and Friends

That’s why the long-imagined Grand Inga on the Congo River: tens of gigawatts of potential keeps returning to policy debates as a continental “super-project.” If designed with modern standards for social safeguards, biodiversity, and climate resilience, Inga-scale hydropower could supply green baseload to multiple regions. The risk is not technical feasibility but governance: ensuring that finance, procurement, and benefit-sharing keep pace with the engineering.

What GERD Can Learn from Akosombo

People First. Akosombo’s resettlement scars argue for sustained, well-funded livelihood restoration, health surveillance (especially for water-borne diseases), and fisheries co-management. Pay the social costs upfront, and keep paying attention.

Operate for Extremes. Build drought and deluge into the operating rules. Publish the rule curves, forecast bands, and spill protocols so communities and downstream water users can prepare.

Design for Trade. Hard-wire regional dispatch. Cross-border lines, fair tariffs, and clear reliability standards turn surplus rainy-season hydropower into firm energy for neighbors, lowering prices and emissions.

Mind the Footprint. A smaller area-to-capacity ratio is good; maintaining shoreline vegetation, clearing biomass where feasible, and monitoring reservoir methane keeps it better.

Share the Data, Share the River. Real-time inflow/outflow data and drought-sharing triggers ideally verified by a neutral platform are the cheapest insurance against crisis diplomacy.

The Bottom Line

GERD is a milestone, not a finish line. It proves that African states can finance and deliver mega-infrastructure that reshapes regional power flows. But a single project cannot electrify a continent. Pair GERD-scale hydro with fast solar and wind, modern grids, storage, and market integration, and Africa can close the access gap faster, and fairer. Meanwhile, Akosombo’s mixed legacy reminds policymakers that megawatts alone don’t make development. Equity, safety, and resilience do.